A SURPLUS BOEING 747 CAN BE CONVERTED AS A DRONE WITH AN ARSENAL OF MISSILES PATROLING AT A DISTANCE OF MORE THAN A 1000 MILES FROM ENEMY TARGET

War Preparation by US Against

Russia and China:Marines Seek Anti Ship HIMARS

The LRSO represents just part of the Air Force’s nuclear modernization efforts. The Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, being developed by Northrop Grumman, is scheduled to have its first flight in 2023. The GBSD is expected to achieve initial operational capability in 2029 and full operational capability with 400 missiles seven years later in 2036. A renewed buildup of Russian troops near the Ukrainian border has raised concern among some officials in the United States and Europe who are tracking what they consider irregular movements of equipment and personnel on Russia’s western flank. At the same time USS Mount Whitney, the flagship of the United States Sixth Fleet, is heading for the #BlackSea. Analysts say the deployment of the warship to show support for #Ukraine. See the full story in the video.

A Marine Corps HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System)

For the first time since December 1941, when Wake Island’s shore gunners sank the invading destroyer Hayate, Marine Corps artillery wants to kill ships. That could be a big boost for the Navy, which confronts ever more powerful Russian and Chinese fleets.

Army artillery is also exploring anti-ship missiles, and the Marines may buy the same one. The difference is that it’s the Marines who work most closely with the Navy and who land in hostile territory to seize forward bases to support the fleet. That role makes Marines the first choice for the first wave, while the larger but slower Army provides backup.

Imperial Japanese Navy destroyer Hayate, destroyed by Marine Corps shore batteries off Wake Island in 1941.

It also means the Marines need a highly mobile system that can come ashore with the grunts and keep moving to evade retaliatory fire while staying connected to Navy fire control networks. That’s a much more demanding mission than static coastal defense, the role of most anti-ship missile batteries around the world from Norway to Japan.

While the Marines haven’t committed to buying anything yet, they have requested information papers from industry, due on Nov. 30th, exploring a wide range of options. It might be the Army’s ATACMs, the Norwegian Naval Strike Missile, or something else. Based on interviews with four Marine officials, however, it’s clear they’d prefer a missile that can be fired from their existing HIMARS launcher, the truck-based High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System. Why? Because even if the Marines buy the minimum of new equipment for this new mission, it’s going to be “incredibly expensive” and tactically challenging.

For a small service like the Marine Corps, anti-ship missiles are “incredibly expensive,” said Kevin McConnell, deputy director of fires and maneuver on the Marine’s Combat Development & Integration staff. “Even if you consider (doing) a coordinated procurement with the Navy, it still becomes something far larger….than anything we’ve ever undertaken for ground (forces).”

Army ATACMS missile launch.

A missile meant to find and a hit moving target, like a ship, is much more costly than one that just has to strike static GPS coordinates. Prices depend on variant and production run, but reported costs for the standard Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) missile, used by both the Marines and Army, range from about $100,000 to $200,000 a shot. The larger Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), fired from the same HIMARS and MLRS launchers, costs roughly $750,000 to $820,000. In contrast, McConnell told me, “your bottom-basement going rate on a Harpoon missile or a Naval Strike Missile is somewhere around $1.5 million.”

But buying the missile is just the start. You need to integrate it with a launcher, a fire control network and a supply chain. Don’t forget training and wargames and staff planning.

A Marine Corps HIMARS (High Mobility Artillery Rocket System)

For the first time since December 1941, when Wake Island’s shore gunners sank the invading destroyer Hayate, Marine Corps artillery wants to kill ships. That could be a big boost for the Navy, which confronts ever more powerful Russian and Chinese fleets.

Army artillery is also exploring anti-ship missiles, and the Marines may buy the same one. The difference is that it’s the Marines who work most closely with the Navy and who land in hostile territory to seize forward bases to support the fleet. That role makes Marines the first choice for the first wave, while the larger but slower Army provides backup.

Imperial Japanese Navy destroyer Hayate, destroyed by Marine Corps shore batteries off Wake Island in 1941.

It also means the Marines need a highly mobile system that can come ashore with the grunts and keep moving to evade retaliatory fire while staying connected to Navy fire control networks. That’s a much more demanding mission than static coastal defense, the role of most anti-ship missile batteries around the world from Norway to Japan.

While the Marines haven’t committed to buying anything yet, they have requested information papers from industry, due on Nov. 30th, exploring a wide range of options. It might be the Army’s ATACMs, the Norwegian Naval Strike Missile, or something else. Based on interviews with four Marine officials, however, it’s clear they’d prefer a missile that can be fired from their existing HIMARS launcher, the truck-based High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System. Why? Because even if the Marines buy the minimum of new equipment for this new mission, it’s going to be “incredibly expensive” and tactically challenging.

For a small service like the Marine Corps, anti-ship missiles are “incredibly expensive,” said Kevin McConnell, deputy director of fires and maneuver on the Marine’s Combat Development & Integration staff. “Even if you consider (doing) a coordinated procurement with the Navy, it still becomes something far larger….than anything we’ve ever undertaken for ground (forces).”

Army ATACMS missile launch.

A missile meant to find and a hit moving target, like a ship, is much more costly than one that just has to strike static GPS coordinates. Prices depend on variant and production run, but reported costs for the standard Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) missile, used by both the Marines and Army, range from about $100,000 to $200,000 a shot. The larger Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), fired from the same HIMARS and MLRS launchers, costs roughly $750,000 to $820,000. In contrast, McConnell told me, “your bottom-basement going rate on a Harpoon missile or a Naval Strike Missile is somewhere around $1.5 million.”

But buying the missile is just the start. You need to integrate it with a launcher, a fire control network and a supply chain. Don’t forget training and wargames and staff planning.

“This type of mission is well beyond anything Marine artillery currently does, so, in some regards, in my opinion, finding the right piece of ordnance is the easy part,” said Pete Dowsett, the senior analyst for HIMARS in the Fires program at Marine Corps Systems Command. “The more complicated part is the logistics tail… the training…how do those fire missions come from a sensor that we’re not normally linked to…. It’s a pretty complex problem.”

Above all, the Marines told me, their new anti-ship mission must work with and for the Navy. That requires “integration into the naval cooperative engagement network,” McConnell said. “I can’t fathom trying to locate and shoot at ships without the Navy running that show.”

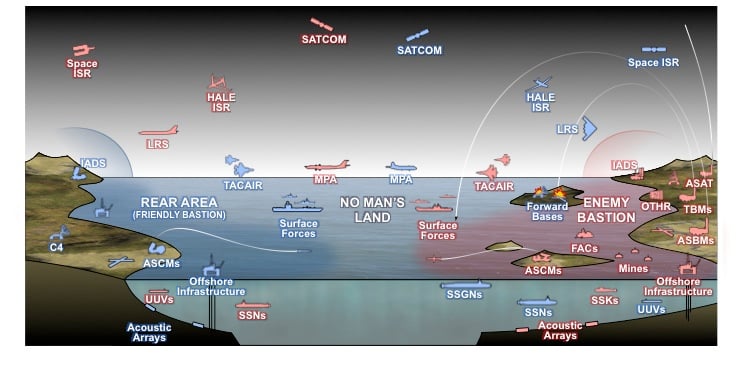

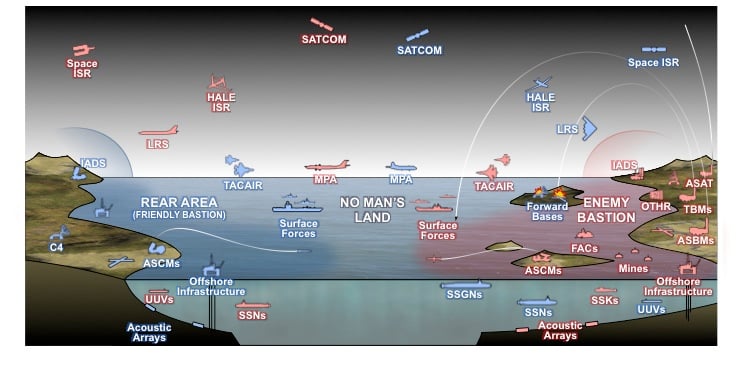

A notional future naval battle (CSBA graphic)

Serving the Navy

For decades, the Navy has helped Marines land and fight ashore — as far inland as Afghanistan. Now the Marine Corps wants to return the favor by helping clear the seas.

“This type of mission is well beyond anything Marine artillery currently does, so, in some regards, in my opinion, finding the right piece of ordnance is the easy part,” said Pete Dowsett, the senior analyst for HIMARS in the Fires program at Marine Corps Systems Command. “The more complicated part is the logistics tail… the training…how do those fire missions come from a sensor that we’re not normally linked to…. It’s a pretty complex problem.”

Above all, the Marines told me, their new anti-ship mission must work with and for the Navy. That requires “integration into the naval cooperative engagement network,” McConnell said. “I can’t fathom trying to locate and shoot at ships without the Navy running that show.”

A notional future naval battle (CSBA graphic)

Serving the Navy

For decades, the Navy has helped Marines land and fight ashore — as far inland as Afghanistan. Now the Marine Corps wants to return the favor by helping clear the seas.

Oshkosh Expects Lower Defense Revenue As JLTV Buying Slows

Even 10 years ago, the Navy didn’t need the help. Now it does. Regional powers like Iran threaten coastal waters with shore-based missiles and short-ranged but high-speed patrol boats. Near-peers like Russia and China boost their ocean-going battle fleets with submarines, destroyers, and even aircraft carriers.

“For the past 70 years, the US Navy has had undisputed sea control when it wanted. That’s no longer the case,” said Art Corbett, who works in the concepts division of the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. For the Marines, he said, “the last time we fought for sea control with the Navy was the Solomons campaign” in 1942.

US and Russian warships

The two services’ joint concept for Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment (LOCE, pronounced “Loki”) is reviving this concept of Marines supporting the fleet. “Any time Marines are going to be pointing missiles seaward, we’re going to be doing this, probably, at the direction of and in coordination with the Navy,” Corbett said. “This is… a naval, networked capability.”

Sharing targeting data with the fleet, Marine Corps anti-ship missiles would be in many ways an extension of the Navy’s Distributed Lethality concept. Distributed Lethality seeks to upgun every possible platform at sea — “if it floats, it fights” — including lightweight Littoral Combat Ships and even currently unarmed auxiliaries, to multiply both the Navy’s options and an enemy’s problems.

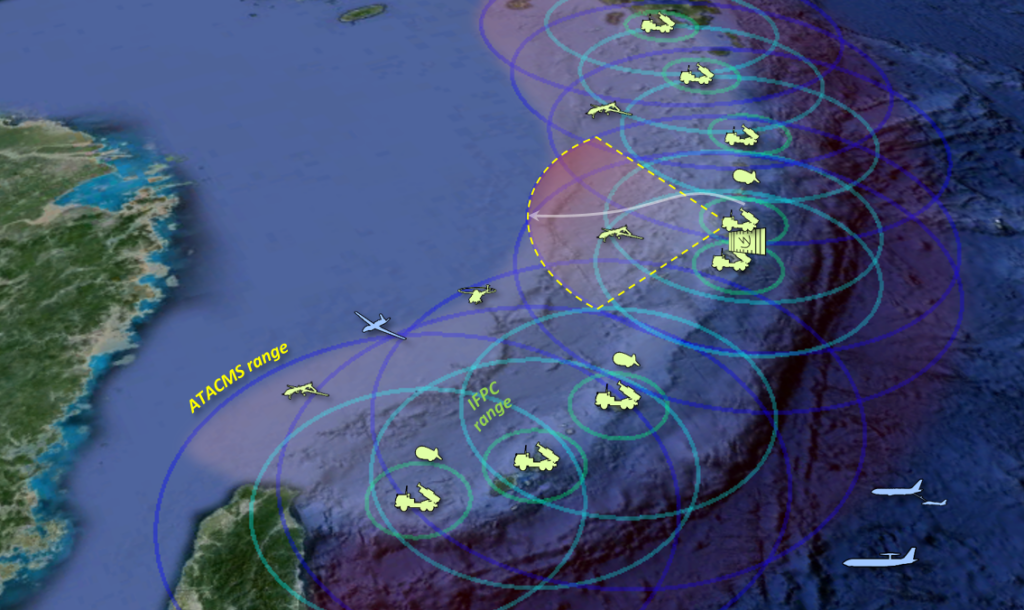

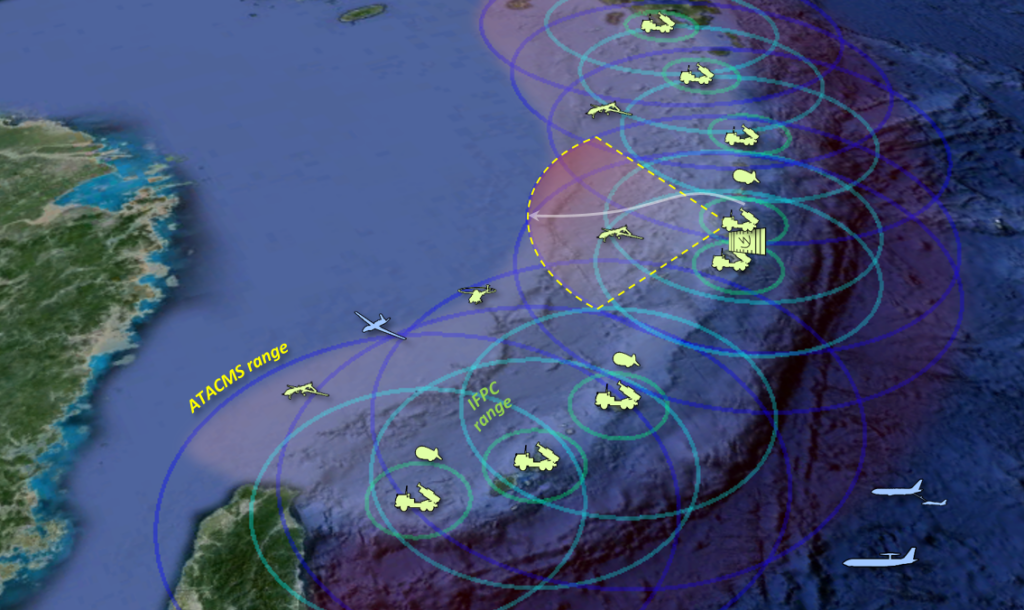

The Marines would provide additional “distributed” firepower from Expeditionary Advance Bases. Carved out of hostile territory by landing forces, kept small and camouflaged to avoid enemy fire, EABs would support F-35B jump jets, V-22 tiltrotors, and drones, as well as anti-ship missiles for the fleet. It’s a high-tech version of Henderson Field on Guadalcanal (part of the Solomons) in 1942. Like Henderson Field, the EABs would provide a permanent presence ashore, inside the contested zone, to support Navy ships as they move in and out to raid and withdraw. The forces ashore are the anvil; the fleet is the hammer.

Shore-based anti-ship missiles wouldn’t be as mobile as ones on ships. But they might be more survivable. Islands don’t sink, after all. Plus, especially in jungle, mountainous, or urban terrain, the land provides far more hiding spaces for a truck-sized HIMARS than the open sea provides for a 400-foot-long ship. Once you launch a rocket, however, the enemy can see your location on radar and infra-red, so the missile batteries must practice “shoot and scoot” tactics: move to a firing point, launch, and move again to a hiding place before enemy retaliation rains down.

Executing such operations in practice, however, requires specialized and costly technology.

Land-based missiles fired from Expeditionary Advance Bases (EABs) could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

Technology & Its Limitations

The good news is that lots of friendly countries already have shore-based anti-ship missiles. The bad news is they may not fit with how the Marine Corps wants to operate: mobile, flexible, and aggressive.

The Marine Corps Request For Information asks for the state of the art because “we know many nations around the Pacific, many in Europe…have all had this kind of capability for decades,” McConnell said. “We would like to make sure it aligns with the Marine Corps concepts of being expeditionary, being able to move at will and being transportable by a variety of means. That was the subject of the RFI.”

“Several nations…. have created this standalone capability,” McConnell said (emphasis ours). “They command and control the missile, the radars, the sensors, in a unit that (only) does that kind of mission, that is permanently oriented on — to use an old term — coastal defense.”

“That kind of exquisite solution” — tailored for a single mission — is probably too expensive and too inflexible for the Marines, McConnell continued. Neither the Marines nor the Army can create a whole new type of unit for “a niche capability,” he said. Instead, the goal is to add anti-ship capability to existing rocket artillery without taking away any of its current capabilities to strike targets ashore.

There are two ways to do this, said Joe McPherson, deputy program manager for fires (i.e. artillery) at Marine Corps Systems Command: “One is modifying our existing missiles and the other would be trying to attempt to bring in missiles that already do this mission.”

The LCS Coronado test-fires a new anti-ship missile from Norway’s Kongsberg.

Preferably, any new missile would be able to fire from the existing Army and Marine Corps launchers, the wheeled HIMARS and tracked MLRS. “I wouldn’t at this point exclude something like Raytheon-Kongsberg Naval Strike Missile,” said McConnell. “There is a potential that it’s capable of being modified to fire from a HIMARS.”

The Kongsberg NSM is competing for the Navy’s Over-The Horizon (OTH) weapon, which will go on the Littoral Combat Ship and future frigates. The Marines are working closely with the Navy, McPherson told me, and the specifications they’ve set are sufficiently close to the Marine Corps’ needs that “whatever missile they pick” is worth considering for a joint buy, which would significantly reduce costs.

Another potential joint buy is with the Army. In the short term, the Army and the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office are upgrading the ATACMS, the biggest missile the HIMARS and MLRS can launch, with a range of roughly 187 miles. The long-term solution might be the Army’s Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) missile, supposed to be be half the size with 67 percent more range.

However, the Marine Corps RFI only asks for “ranges of 80 miles or greater,” which means they are at least considering lighter, cheaper missiles that a unit could carry more of, trading range for staying power. The Marines are also willing to consider a less sophisticated and therefore less expensive warhead: one good enough to destroy small craft, like missile boats, and damage larger vessels, but probably unable to penetrate the defenses of a full-size warship with sufficient precision to deliver a killing blow.

Bryan Clark

“That might be the capability we end up with,” McConnell told me. “That might be enough.” (Especially, I might add, if Army units fire longer-ranged ATACMS or LRPF missiles from further back).

Would an 80-mile missile be useful? Absolutely, said Bryan Clark, a retired Navy commander now with the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. “The 80 (nautical mile) minimum range could be relevant in scenarios in the Persian Gulf, Mediterranean, and possibly the South China Sea,” all relatively narrow waterways, he said. “That would be enough to threaten ships beyond realistic ranges for enemy helicopters and assault craft to attack the EAB (in retaliation).”

The downside is that even an 80-mile missile would need a relatively large launcher, like the HIMARS, and despite having “High Mobility” in its name, Clark is not sure the 12-ton truck is mobile enough for Expeditionary Advance Base operations. (The tracked MLRS is more mobile over rough terrain but weighs 22 tons). “I hope responses to the RFI will address mobility of the fires launcher,” he said.

“The main thing we’re looking for is really what’s in the realm of the possible, both near-term solutions and far-term,” McPherson said of the RFI. Once the data comes back in December, the Marine officials said, they’ll look at their options and start work on an official requirement.

Even 10 years ago, the Navy didn’t need the help. Now it does. Regional powers like Iran threaten coastal waters with shore-based missiles and short-ranged but high-speed patrol boats. Near-peers like Russia and China boost their ocean-going battle fleets with submarines, destroyers, and even aircraft carriers.

“For the past 70 years, the US Navy has had undisputed sea control when it wanted. That’s no longer the case,” said Art Corbett, who works in the concepts division of the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. For the Marines, he said, “the last time we fought for sea control with the Navy was the Solomons campaign” in 1942.

US and Russian warships

The two services’ joint concept for Littoral Operations in a Contested Environment (LOCE, pronounced “Loki”) is reviving this concept of Marines supporting the fleet. “Any time Marines are going to be pointing missiles seaward, we’re going to be doing this, probably, at the direction of and in coordination with the Navy,” Corbett said. “This is… a naval, networked capability.”

Sharing targeting data with the fleet, Marine Corps anti-ship missiles would be in many ways an extension of the Navy’s Distributed Lethality concept. Distributed Lethality seeks to upgun every possible platform at sea — “if it floats, it fights” — including lightweight Littoral Combat Ships and even currently unarmed auxiliaries, to multiply both the Navy’s options and an enemy’s problems.

The Marines would provide additional “distributed” firepower from Expeditionary Advance Bases. Carved out of hostile territory by landing forces, kept small and camouflaged to avoid enemy fire, EABs would support F-35B jump jets, V-22 tiltrotors, and drones, as well as anti-ship missiles for the fleet. It’s a high-tech version of Henderson Field on Guadalcanal (part of the Solomons) in 1942. Like Henderson Field, the EABs would provide a permanent presence ashore, inside the contested zone, to support Navy ships as they move in and out to raid and withdraw. The forces ashore are the anvil; the fleet is the hammer.

Shore-based anti-ship missiles wouldn’t be as mobile as ones on ships. But they might be more survivable. Islands don’t sink, after all. Plus, especially in jungle, mountainous, or urban terrain, the land provides far more hiding spaces for a truck-sized HIMARS than the open sea provides for a 400-foot-long ship. Once you launch a rocket, however, the enemy can see your location on radar and infra-red, so the missile batteries must practice “shoot and scoot” tactics: move to a firing point, launch, and move again to a hiding place before enemy retaliation rains down.

Executing such operations in practice, however, requires specialized and costly technology.

Land-based missiles fired from Expeditionary Advance Bases (EABs) could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

The good news is that lots of friendly countries already have shore-based anti-ship missiles. The bad news is they may not fit with how the Marine Corps wants to operate: mobile, flexible, and aggressive.

The Marine Corps Request For Information asks for the state of the art because “we know many nations around the Pacific, many in Europe…have all had this kind of capability for decades,” McConnell said. “We would like to make sure it aligns with the Marine Corps concepts of being expeditionary, being able to move at will and being transportable by a variety of means. That was the subject of the RFI.”

“Several nations…. have created this standalone capability,” McConnell said (emphasis ours). “They command and control the missile, the radars, the sensors, in a unit that (only) does that kind of mission, that is permanently oriented on — to use an old term — coastal defense.”

“That kind of exquisite solution” — tailored for a single mission — is probably too expensive and too inflexible for the Marines, McConnell continued. Neither the Marines nor the Army can create a whole new type of unit for “a niche capability,” he said. Instead, the goal is to add anti-ship capability to existing rocket artillery without taking away any of its current capabilities to strike targets ashore.

There are two ways to do this, said Joe McPherson, deputy program manager for fires (i.e. artillery) at Marine Corps Systems Command: “One is modifying our existing missiles and the other would be trying to attempt to bring in missiles that already do this mission.”

The LCS Coronado test-fires a new anti-ship missile from Norway’s Kongsberg.

Preferably, any new missile would be able to fire from the existing Army and Marine Corps launchers, the wheeled HIMARS and tracked MLRS. “I wouldn’t at this point exclude something like Raytheon-Kongsberg Naval Strike Missile,” said McConnell. “There is a potential that it’s capable of being modified to fire from a HIMARS.”

The Kongsberg NSM is competing for the Navy’s Over-The Horizon (OTH) weapon, which will go on the Littoral Combat Ship and future frigates. The Marines are working closely with the Navy, McPherson told me, and the specifications they’ve set are sufficiently close to the Marine Corps’ needs that “whatever missile they pick” is worth considering for a joint buy, which would significantly reduce costs.

Another potential joint buy is with the Army. In the short term, the Army and the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office are upgrading the ATACMS, the biggest missile the HIMARS and MLRS can launch, with a range of roughly 187 miles. The long-term solution might be the Army’s Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) missile, supposed to be be half the size with 67 percent more range.

However, the Marine Corps RFI only asks for “ranges of 80 miles or greater,” which means they are at least considering lighter, cheaper missiles that a unit could carry more of, trading range for staying power. The Marines are also willing to consider a less sophisticated and therefore less expensive warhead: one good enough to destroy small craft, like missile boats, and damage larger vessels, but probably unable to penetrate the defenses of a full-size warship with sufficient precision to deliver a killing blow.

Bryan Clark

“That might be the capability we end up with,” McConnell told me. “That might be enough.” (Especially, I might add, if Army units fire longer-ranged ATACMS or LRPF missiles from further back).

Would an 80-mile missile be useful? Absolutely, said Bryan Clark, a retired Navy commander now with the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. “The 80 (nautical mile) minimum range could be relevant in scenarios in the Persian Gulf, Mediterranean, and possibly the South China Sea,” all relatively narrow waterways, he said. “That would be enough to threaten ships beyond realistic ranges for enemy helicopters and assault craft to attack the EAB (in retaliation).”

The downside is that even an 80-mile missile would need a relatively large launcher, like the HIMARS, and despite having “High Mobility” in its name, Clark is not sure the 12-ton truck is mobile enough for Expeditionary Advance Base operations. (The tracked MLRS is more mobile over rough terrain but weighs 22 tons). “I hope responses to the RFI will address mobility of the fires launcher,” he said.

“The main thing we’re looking for is really what’s in the realm of the possible, both near-term solutions and far-term,” McPherson said of the RFI. Once the data comes back in December, the Marine officials said, they’ll look at their options and start work on an official requirement.

The Key to Success in War with Russia and China Could Be Missiles

For the foreseeable future, the United States and China are locked in a security competition.

Here's What You Need to Know: Land-based missile batteries can threaten ships dozens or even hundreds of miles away.

No comments:

Post a Comment